Arrival is ambiguous. Both as a word with multiple diametrically opposed, context-dependent meanings … and also as an embodied social experience. Even if we humans did not have the capacity of grammatical, meaning-generative language to communicate with one another, our socially intensive, long lives entail that we would experience arrival in a much more variable array of manifestations, which would become thoroughly entangled in more complex memories, than do our closest ape relatives or would have our Miocene ape ancestors.

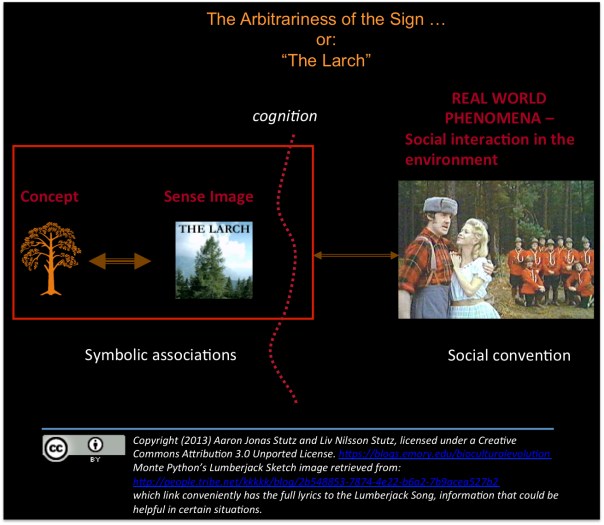

But we do have language. We construct stories and webs of symbols out of the underlying symbolic structure of grammatical, meaning-generative language(s), which we begin to learn already in our first months of life. And the word “arrival” (and its close translations in other natural languages) is an example of how referential symbols, even when they have many different meanings that could easily be confused in everyday social situations, focus our thoughts. Meaningful symbols direct our attention and often help us sustain it, as we continue to think and act. The symbols we use in everyday life don’t always have clear referents. When we begin tell a story about arrival, different listeners may start to imagine or assume how the narrative will unfold. It might be imagined as a story about arriving someplace new, about growth, challenge, discovery. Or as a story about return. It might be a routine arrival, part of a regular cycle of departure and return. Or it might be truly unusual, a once-in-a-lifetime experience. Using the efficient symbolism of the same word, “arrival,” for all of these different patterns, each instance of which would inevitably be constituted by unique circumstances, our imaginations exploit this arbitrary common thread tying together the successive experience of different arrivals with the experience of remembering or telling about arrivals. And thus, symbolic language helps us remember, helps us to imagine the similarity and difference between self and other, helps us to connect disparate experiences that might be separated by decades. Helps us to connect our own experiences to fictional events or abstract notions related to arrival: beginning, ending, the cyclical and recurring, the temporally directional and changing, the known and unknown, the forgotten and remembered.

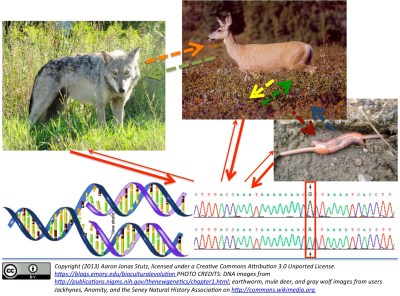

I would suggest that the use of words–whether initially constituted by learned hand-gesture or vocalization sequences–would have been favored by natural selection, for pointing toward concrete states of affairs quite immediately relevant for bodily homeostasis and that of kin on an hourly or daily basis (monitoring for predators and dealing with hunger, thirst, thermoregulatory balance, exhaustion, caring for dependent juvenile offspring). Symbolic pointing, as Michael Tomasello (2008) has so eloquently and rigorously argued, allows the individual to influence the attention of others, and with eye-contact and constant monitoring, spoken discourse allows dyads or larger groups to manage joint attention. And this would be particularly advantageous for survival in a more open vegetation pattern in the terrestrial habitat that our ardipithecine and australopithecine ancestors had adapted to between ca. 7 – 3 million years ago in East Africa. Especially when food and water resources were diverse, heterotrophic, and often difficult to find and extract. Simple noun utterances referring to people, things, and actions could be combined with bodily gestures and gaze direction to negotiate small-group movement and activity in the hominin omnivorous, terrestrial, extractive niche that was then evolving. But arbitrary word symbols–taken by learned convention to point toward something quite concrete, like a particular kind of fruit, seed, or animal prey–can easily acquire a more general, ambiguous, or abstract referent in a socially intense environment, as long as the speakers maintain the word-symbol usage. The initial evolutionary limitation for cultural increase in lexicon size in late Pliocene or Pleistocene hominin groups would have been on the anatomical, time, energetic, and social cost of sending or understanding a message. But there would have been persistent selective pressure favoring more efficient, rapid, varied utterances and more effective understanding and memory, simply because being able to learn and point to more particular kinds of situations in the near environment would enhance survival and reproductive success. And because such simple linguistic pointing to nearby, recently witnessed or soon-hoped-for states of affairs in the environment would reinforce mutual monitoring and cooperation, the resulting increase in sustained social interaction and joint attention would support learning of words for general categories of food, pronouns, and basic but environmentally compassing events, like sunrise and sundown … or social states of affairs, like arrival.

And with learning of such symbols pointing to general phenomena that sit in a higher nested hierarchical relationship to specific events or things (“arrival,” “animals,” “plants,” “food,” “stone,” “baby,” “adult”), our hominin ancestors would have been able to focus their imaginations and memories on stories or scenarios in which self is compared with other. This, even before natural selection would have favored further cognitive processing power to learn many additional symbolic grammatical items, so that such imagined or remembered stories could be uttered and shared. Whether this evolutionary process took place relatively earlier or later, slightly more quickly or more slowly, it would have been a gradual one. But the evolution of our linguistic capacities would have co-occurred with the construction of our niche as a conspicuously socially intense one. There would have been a positive, reinforcing feedback in natural selection, favoring the capacity to learn and to send more–and more varied–symbolic messages, and these with more varied referents … in turn, favoring the networks of sustained social relationships in which these symbols and their variable referents would have been invented, learned, and exploited. And in this context favoring participation in larger social networks with more sustained, interdependent social relationships, the embodied and logical focusing effect of arbitrary symbols, which sustain an individual’s attention in imagination on patterns of shared experience with others, would have supported the evolutionary emergence of “theory of mind” and empathy. A new person I’ve never met before has just arrived in the valley. How would I feel if I were the stranger arriving, hungry, tired and thirsty, in a new group?

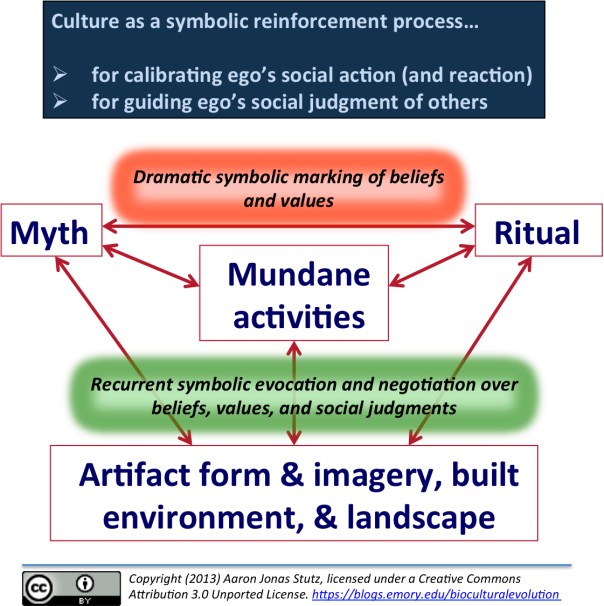

But more general, abstract words–with their multiple, context-dependent referents, however learned and sustained through interaction in multiple, complex, intense, constantly negotiated, interdependent social relationships–are ambiguous. Language helps us to adapt socially to a really complex niche. We can share information about parts of the environment beyond what we can immediately see, hear, or smell … And we can plan jointly with others, cooperating to exploit resources in those out-of-immediate-reach parts of the environment. The arbitrary nature of words as polysemous symbols has a more surprising logical effect. In focusing the imagination, abstract words like “arrival” can logically support or evoke thoughts that constitute human consciousness, in fundamentally contrasting existence with non-existence, being with nothingness, life with death as the negation of life. And this would in turn produce the individual’s consciousness of family and society as constituting the universe, existence of the world. This is fundamental to understanding why human culture is more than just learning and information sharing. Culture is also the process of consciousness logically leading us to construct narratives and images of the social relationships on which we depend as integrally tied to cosmological order. And these stories and images move us.

REFERENCES

Tomasello, M. (2008). Origins of Human Communication. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press.