by Aaron Jonas Stutz

A recent article published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences statistically demonstrates something that is bound to get environmental determinists excited.

Here it is:

Human cultures incorporating concepts of “moralizing high gods” tend to exist in relatively harsh environments.

Of course, the authors of the study (Botero et al., 2014) cautiously point out that the relevant data consist of statistical patterns. And that the societies under study are constituted by human beings. There have to be multiple interacting factors at play, Botero and colleagues state. I mean, we’re talking about a rather complex pattern of cultural development: whether “moralizing high gods” concepts and representations have already reached historical widespread adoption and intergenerational persistence within a community.

Yet, the authors are clear about their theoretical perspective on the data:

In general, our findings are consistent with the notion that a shared belief in moralizing high gods can improve a group’s ability to deal with environmental duress and may therefore be ecologically adaptive … (Botero et al. 2014: p. 3)

From an interdisciplinary perspective, a wide range of experimental, historical, and ethnographic evidence supports sound theoretical argument. This is a darn plausible hypothesis.

And it’s certainly nice to document–with a robust pattern of scientific observation–support for the “environment influences religion” hypothesis.

This result will certainly not please everyone. Botero et al.’s (2014) study will effectively pull on a salient contemporary cultural tension, which exists between our own conflicting beliefs about agency and freedom versus genetic or environmental inevitability.

But that cultural tension is not really salient for a comprehensive and consistent understanding of how religious beliefs persist or change in a culturally constituted environmental context. How can that really be? The main result seems to be a pretty clear point for the environmental determinism side.

What remains implicit in the study’s theoretical framework–but what warrants the authors’ point that many interlinked factors have to be involved in shaping cross-cultural variation in the religious structuration of moral commitment–is that there are multiple, historically dependent ways that large-scale societies can hold themselves together over many generations, in very challenging ecological conditions.

Basically, “moralizing high gods” are just one of many cultural possibilities for religious systems of moral commitment … even in harsh, unpredictable, low-biomass-production environments.

It’s just that, recently, there are many cultures from around the world that are documented to have concepts of “moralizing high gods” … AND they tend to associate–a bit statistically more, than not–with such difficult environmental settings.

It is a central lesson of anthropological research that, in our shared global humanity, we are part of a very well-documented cultural diversity in:

- religious life, belief, and ritual practice

- their systemic interrelationships with dispositions and values about moral commitment and judgment

It should not be a surprising result that, as part of this diversity, religion can change dynamically over time, a component of culture as adaptation.

To put it a bit technically, each of us develops culturally structured embodied ontological commitments. Our religious environment can shape our actions and thoughts. It can do so in a variety of ways, over multiple time and social-network scales. Cultural structuration involving religious systems of practice can shape similar patterns of action and thought across generations.

In turn, our moral or religious sense of commitment to certain sociopolitical interests–from the family level of interpersonal relationships … to inter-societal interaction, exchange and conflict–can contribute to long-term effects on the very social and technological underpinnings of economic production and consumption … and even to biological reproduction. Thus, some societies have come to incorporate religiously infused moral values and dispositions involving concepts of “moralizing high gods.” Some have not. Botero et al. (2014) demonstrate that societies with certain shared religious beliefs have historically been especially good at settling in and holding onto territory that does not yield terribly reliable sources of food.

If Not Environmental Determinism, Then What?

So far, my point has been to move beyond fretting over whether environmental conditions–under some historical situations–have effectively sifted out certain religious systems, favoring others. Basically, this is also the point to which Botero et al. (2014) bring us. They establish scientifically that the following questions should be in play in ongoing inquiry about how culturally constituted, shared religious beliefs and practices come to vary between societies, across geographic space, and over time:

- In general, how much are our cultural values, beliefs, and loyalties the result of historical accident?

- How much are they the result of adaptive cultural-trait-group-level fit to the eco-physical environment?

- Or … how much are they the result of sociopolitical and economic power struggles–involving shifting alliances and conflicts–that can shape a society’s organizational complexity and political control?

- More specifically, when environmental factors are imposing selective pressure on culturally constituted religious systems, is it actually religious belief that increases a society’s resilience in harsh environments, or is there an as-yet-unidentified factor that associates with religion that plays the main adaptive role?

- And what are moralizing high gods anyway?

The first three are such defining questions for anthropology–and for the discipline’s scholarly relevance for broader social science, ecological, and evolutionary biological inquiry.

Franz Boas and Claude Lévi-Strauss tended to emphasize their own particular (and often quite particularistic) expectations. Cultural variations between human communities reveal such diversity and local originality, they suggested, that it’s best to chalk up how those differences emerged to finely intricate, equally diverse historical contingencies. Thus, they thought that question (1) was the interesting one. But they were cultural anthropologists, mainly interested in ethnographic sources of observation. They were focused on how living human societies are culturally diverse. Not how they got to be so diverse over centuries and millennia.

Thus, over the last half of the 20th Century, questions (2) and (3) also came into focus. The topics of cultural adaptation and evolution in sociopolitical complexity continue shape archaeological and anthropological research. Yet, how to balance all three questions remains pretty hotly debated (see Gremillion et al. [2014] on biocultural evolution as a systematic selective process, along with published responses by Zeder [2014] and Smith [2014]).

Just to reiterate, we’re at the point where we know better what the questions are … but no clear answers yet.

In fact, questions (4) and (5) are basically reminders that we need to be scientifically rigorous in our inquiry. We’re still working on getting answers, and we need to be very cautious not to, well, jump to conclusions. Although a lot of recent research in the social sciences has focused on how belief in “moralizing high gods” tends to reinforce the individual’s moral commitment to normative obligations to the collective, especially during times of stress, it remains important not to lose focus on how questions 1-3 fit together, whatever the temptation to infer that it’s all about adaptation (that is, all about question 2).

Biased Scientific Attention to Western Moralizing High God(s)?

I will be even clearer about what I’m cautioning. It is important for Western-based athiest or agnostic scientists not to give biased, inflated importance to religious systems involving “moralizing high gods.” The thing is, those moral-religious systems–part of Jewish, Christian, and Muslim monotheistic traditions–are the ones that many of us scientists, our parents, or grandparents have already grown away from, as we have become more secular, often making us different in our own moral values and commitments from many–if not the majority of–others in our own societies. We thus have to be very careful to make sure we’re not just trying to figure out why there could be such differences in belief–and differences in inspiration and support for moral commitment–within our own very large, complex societies.

Just to show why concerns about subtle, implicit bias are real, consider this. Cultures in the Ethnographic Atlas database (Murdock, 1967; Gray, 1999) that are recorded as incorporating “moralizing high gods” are relatively rare. Out of 748 distinct societies for which ethnographic data on “high gods” has been recorded, only 181–or just under 25%–have beliefs or myths about high deities (as opposed to nearly-earth-bound spirits or ancestors) who are “supportive of human morality.” The other 75% of societies do not have beliefs or representations of high divine beings who pass judgment on, support, or punish flesh-and-blood humans. In fact, 37% of all societies (and thus, nearly 49% of those cultures without moralizing deities) do not have high gods at all.

When we talk about cultural diversity–especially when it comes to religious belief and practice–the vast majority of variation in religious experience that people over the past 100-200 years have had would be found among societies that lack explicit shared concepts or representations of “moralizing high gods.”

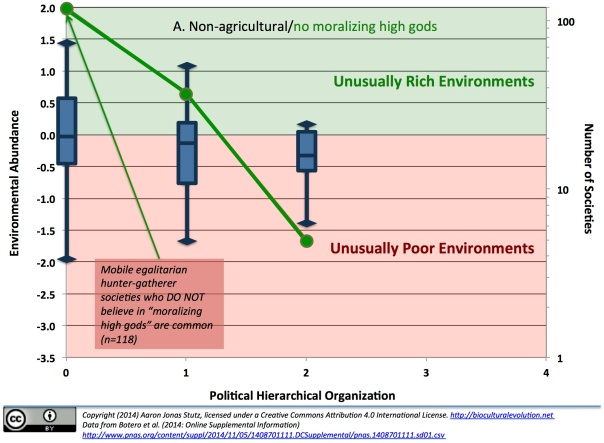

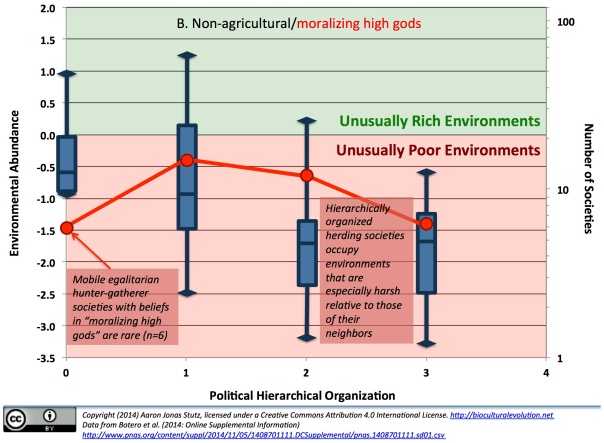

Restricting our consideration to the 124 small-scale, politically egalitarian, and decentralized foraging societies included in Botero et al.’s dataset (see Murdock [1967] and Gray [1999]), we may observe that only six are reported to hold beliefs or representations about moralizing high gods.

If we are interested in understanding how religious beliefs, commitments, and practices emerged as cross-culturally near-universal features of human social life, it makes more sense to focus on cultures with practices involving non-moralizing deities, spirits, and ancestors.

We could take this even further. Without combing through the ethnographic sources on societies with “moralizing high gods,” we have little idea about why such notions are so culturally rare. Such a detailed ethnographic search would be informative. In the meantime, it is reasonable–in the absence of other clear evidence–to expect that virtually all recent cultural manifestations of “moralizing high gods” are part of Jewish, Christian, and Muslim traditions spread geographically through diasporas, proselytization, or forced conversion.

Figuring Out Why Some Cultures Came to See God(s) as High Moral Judges?

In this light, there is one (relatively, as these things go) simple hypothesis that may prove to explain the statistical association of “moralizing high gods” with harsh environments. Such cultural beliefs are generally adaptive in culturally constructed niches that involve very high system complexity, involving tension and synergy between hierarchically organized central political control–at least in certain contexts, like mobilization for raiding and warfare–and decentralized heterogeneity in the organization of economic production, exchange, and consumption.

After all, the monotheistic “moralizing high god” tradition that Judaism, Christianity, and Islam encompass is geographically centered on southwestern Asia and the eastern Mediterranean. This area is defined not by harsh environments per se, but abundant, often very sharp ecological gradients and boundaries between very productive and very poor environmental zones. Individual religious practice in this tradition conspicuously involves portable cultural support for: ritually approaching the divine; reflecting over divine judgment of actual human morality; and publicly commenting on or reaching social judgments of self and others, framed by consideration of divine judgment. Yet, individual religious practice in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam also involves participation in much larger collective, socially intense rites of passage, seasonal feasts, and prayer and sermon rituals. And these also maintain the common thread of divine expectation, judgment, mercy, and punishment, based on omniscient knowledge of how individuals act toward one another and toward the divine. Consequently, concerns over moral judgment and decision-making in all areas of everyday experience tend to be religious concerns, not about purity or ancestral devotion or fortune or fate or the evil eye … but about divine judgment, reward, or punishment. And it is the multi-scalar socio-religious practice of acknowledging, accepting, and offering thanks for divine judgment that metaphorically models and mediates the individual’s obligations to the collective, represented and ruled by centralized political institutions. I am suggesting that, to the extent that environmental factors have exerted long-term selective pressures on the variety of religious sentiments and expressions that arise in all forms of cultural discourse, “moralizing high gods” may have supported fit between organizationally complex sociopolitical and economic systems and complex territories encompassing heterogeneous environmental zones and transportation paths.

Testing this hypothesis is a task for another day.

If any readers have leads on work that is already investigating this question, please let me know!!!

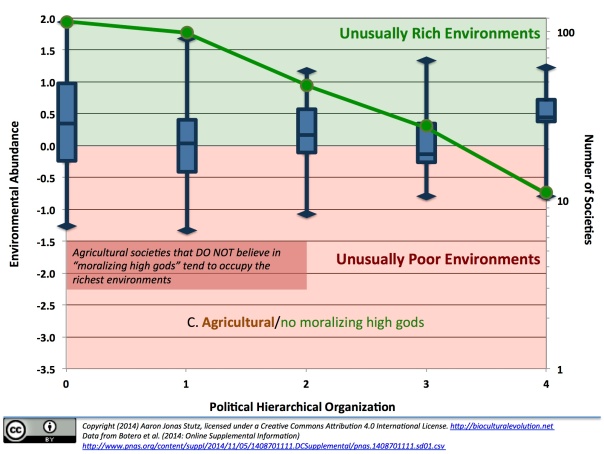

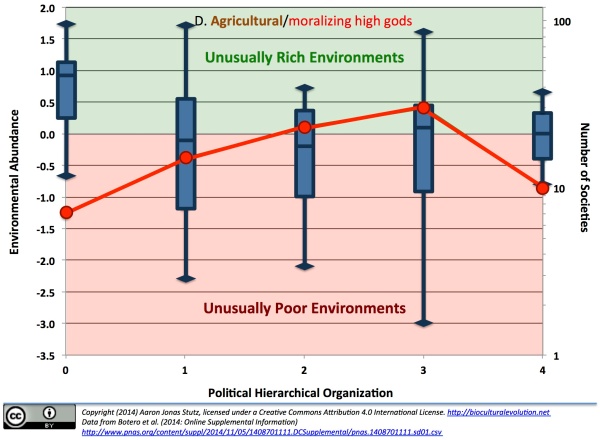

Back to All Those Cultures Without Moralizing Deities

In the meantime, it is worth returning to the question of why so many societies lack beliefs or concepts about “moralizing high gods,” yet they manage to maintain moral values linking the individual to the family … and onto wider institutions, social networks, and conspicuous network boundaries (such as linguistic and ethnic, intentionally monitored borders). The cross-tabulations in the table below come from Botero et al.’s (2014) original data, posted with their open-access article. It includes their sample of 583 distinct societies included in the Ethnographic Atlas, encompassing communities with mainly foraging, herding, agricultural or mixed food acquisition/production economies.

| politically decentralized | centralized hierarchy | Row Totals | |

| non-moralizing deities | 232 | 227 | 459 |

| moralizing deities | 13 | 111 | 124 |

| Column Totals | 245 | 338 | 583 |

The criteria for distinguishing politically decentralized societies from those with centralized hierarchies come from the Ethnographic Atlas (Murdock 1967). Variable 33 is labeled “Jurisdictional Hierarchy Beyond Local Community,” and the ranked values range from complete decentralization (a value of 0) to large states (4). The table above counts societies as decentralized if they were coded as having “no political authority beyond community.” All others (≥ 1) include petty chiefdoms, complex chiefdoms, and states.

The association between political decentralization and non-moralizing deities is hardly random. (For the stats geeks, the results of a Fisher’s exact test yield a two-tailed probability of 2.1 x 10^-17–or pretty much zero–that the cell counts are actually due to random sampling.)

Beliefs in moralizing high gods are indeed especially rare among highly decentralized, egalitarian foragers and small-scale farming societies.

Yet, the converse is not at all true. Beliefs in moralizing high gods are not especially common among more hierarchically centralized societies.

The figures below–also based on Botero et al.’s (2014) original data–confirm that moralizing high gods do have something to do with more hierarchically organized cultures surviving in harsher environments. But not everything.

These figures also reveal that societies without moralizing high gods are particularly good at occupying and holding onto relatively rich, ecologically abundant territories, mainly through agricultural production technologies, but also through foraging or mixed agricultural-herding strategies.

And this is the inference that Botero et al. (2014) missed, even though it was there in plain sight.

We cannot understand the environmental conditions that may have influenced the cultural emergence of “moralizing high gods” without also understanding the extensive, rich, and diverse environmental conditions that have shaped that vast bulk of cultural diversity in the forms of religious life … forms that–however variable from society to society around the world–happen to lack expressions or beliefs in high deities as omnipresent moral judges.

REFERENCES CITED

Botero, C. A., Gardner, B., Kirby, K. R., Bulbulia, J., Gavin, M. C., & Gray, R. D. (2014). The ecology of religious beliefs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 201408701. doi:10.1073/pnas.1408701111

Gray, R. D., Atkinson, Q. D., & Greenhill, S. J. (2011). Language evolution and human history: what a difference a date makes. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 366(1567), 1090–1100. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0378

Gremillion, K. J., Barton, L., & Piperno, D. R. (2014). Particularism and the retreat from theory in the archaeology of agricultural origins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(17), 6171–6177. doi:10.1073/pnas.1308938110

Murdock, G. P. (1967). Ethnographic Atlas: A Summary. Ethnology, 6(2), 109–236. doi:10.2307/3772751

Smith, B. D. (2014). Failure of optimal foraging theory to appeal to researchers working on the origins of agriculture worldwide. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(28), E2829–E2829. doi:10.1073/pnas.1408208111

Zeder, M. A. (2014). Alternative to faith-based science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(28), E2827–E2827. doi:10.1073/pnas.1408209111